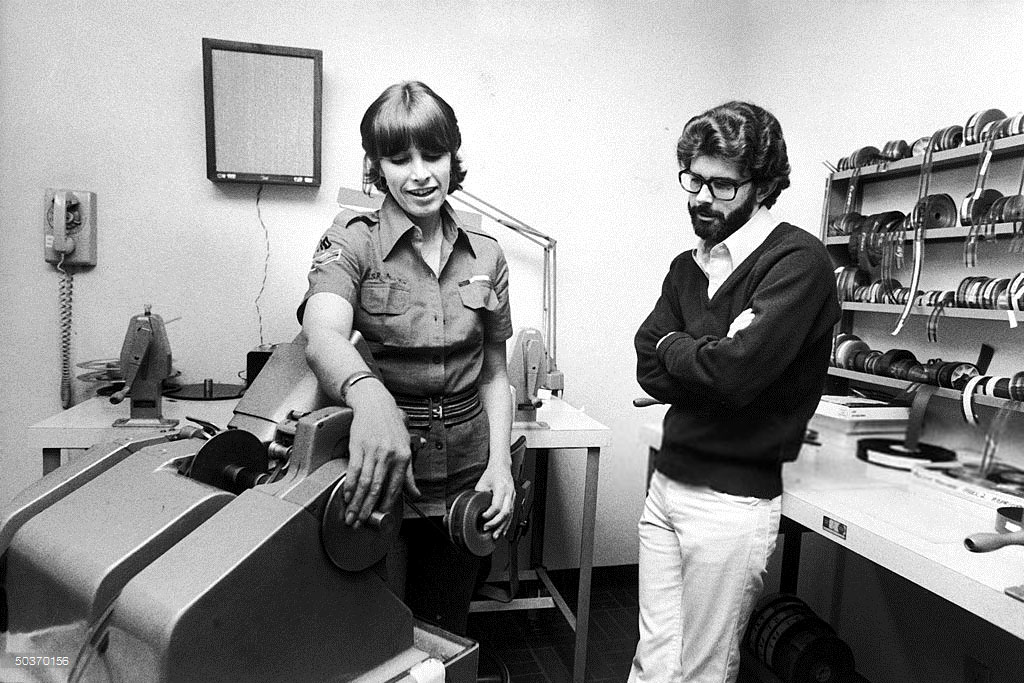

In fact, his very first film, Look at Life, is in all its Arthur Lipsett-inspired glory, very much the product of an editor (or maybe Lucas the editor is the product of it?). And he fell in love with editing in more than one way, even marrying an editor, Marcia Griffin. She had in her own impressive, though short-lived career, worked in various editorial capacities with Scorsese on Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, New York, New York, and Taxi Driver. As well being credited on all of Lucas’s projects after THX 1138, up until Return of the Jedi (though realistically, she probably worked on, or at least influenced his works as far back as USC, where they first met). Her role in Lucas’s life is often downplayed, and has only received scant coverage, despite her central role in it all. With one notable exception.

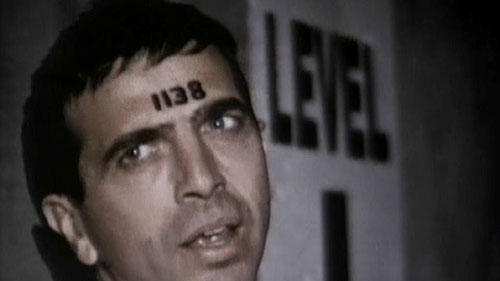

Looking back now, a clear pattern emerges: Lucas's friend Matthew Robbins wrote the original THX 1138 4EB treatment[3], and Lucas collaborated with classmate Walter Murch on the follow-up feature-length version, THX 1138. He wrote American Graffiti with help from friends Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, who would go on to help on Star Wars (which took four years to write, and by all accounts, not a day of which was pleasant for him), as well as The Temple of Doom. Indiana Jones was conceived by Lucas, but fleshed out in sessions with Spielberg and Lawrence Kasdan[4], who would go on to write the screenplay. Leigh Brackett has story credit on The Empire Strikes Back, though her draft resembles little of the final product, and seemingly Lucas wrote the basic outline, which Lawrence Kasdan then filled in. A template that probably ended up much the same for Return of the Jedi, though here Lucas’s hand seems to weigh heavier.

The world of THX 1138 was conceived by Matthew Robbins, American Graffiti was autobiographical, Star Wars grew from Flash Gordon and Indiana Jones from serials and adventure films.

Understanding this part of Lucas is the cornerstone to understanding the themes of his work, from his very first student film and onward. It’s why his thematic underpinnings are often as basic as they are, which in turn is often claimed by critics to be one of his many failures as a storyteller. But these basic themes and motifs are also his greatest strength as a storyteller, as evidenced by the prequel trilogy in which Lucas strayed from the path, and fared less successfully.

Furthermore, as progressive as he’s been for the technical side of cinema, he’s a conservative (in the more traditional sense of the word) in so many other areas, as the themes of his work so clearly show. And pre-Star Wars interviews reveal that rather than changing over the years, he has simply managed to achieve exactly what he set out for, and his themes reflect just that.

Lucas knows this more than anyone, and after Star Wars even went so far as to ‘retire’ from directing:

“I’ve retired from directing,” Lucas says. “If I directed Empire, then I’d have to direct the next one and the next for the rest of my life. I’ve never really liked directing. I became a director because I didn’t like directors telling me how to edit, and I became a writer because I had to write something in order to be able to direct something. So I did everything out of necessity, but what I really like is editing.”[p35, 5]

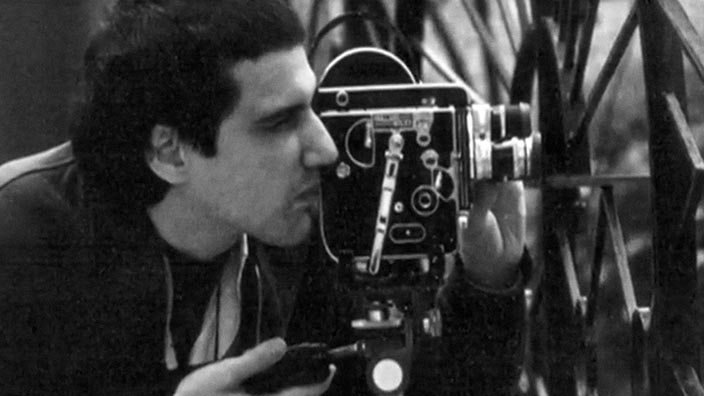

The editing act, of combining several pieces of film that may or may not be directly related, into a new piece, is the act of creation—of synthesis; combining several existing ideas into a new one—made corporeal. And Lucas is very much an editor, not only in the actual film-industry meaning of the word, but in his approach to creation, in borrowing sequences, scenes, character traits and costumes from a wide spectrum of sources, and combining them into something new.

The Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises are well known for drawing on the films and TV serials of old, but even going back to his student films, Lucas was always drawing heavily on external sources of ideas to create, sometimes less obvious, some times more so. His work as a writer and a film maker in general, is all about montage and collage, because that’s where he came from. His earliest, and perhaps most important inspiration of all, was after all Arthur Lipsett, the uncrowned king of montage and collage.

Editing—montage, collage and juxtaposition of film—is also, of all the torturous parts of the filmmaking process, the only one George Lucas seems to really enjoy. And of course, apart from writing, which he openly despises, the editing process is the part of filmmaking that comes closest the careless camaraderie of his student days at USC. A time Lucas has sought back towards ever since graduating, most notably of course with the construction of Skywalker Ranch.

Lucas was indeed always an editor, through and through, not only in how he assembles and works throughout the production and post-production, but also in how he conceives of his films, and how they come together in pre-production. It’s a trait manifested more and more with every film he made.