“At the NFB and around the world, we pushed our cameras and film stock to the limit. When we made 60 cycles, we used a 1000 mm lens from NASA that was more than 1 metre wide. The images were extremely compressed, and that became the first shot of the movie. That film really rocked the boat. It was essential viewing.” [2]labrecque

To Lucas it must have been a revelation. He would go on to make wide use of long lenses, from this, his first serious attempt at a cohesive piece of film, up through all of his films. The lineage from 60 cycles through 1:42.08 to THX 1138, all of which share the use of extreme long shots held for in place for extended periods of time is particularly clear. It’s a technique also widely used by several of Lucas’s other favorite filmmakers, the likes of David Lean, John Ford, Sergio Leone and of course Akira Kurosawa.

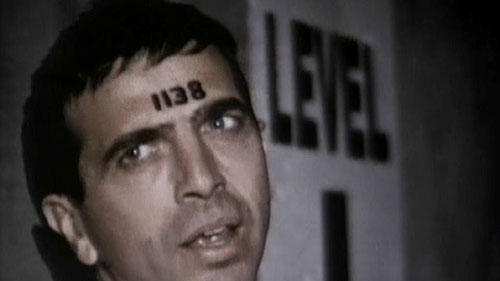

Where wide lenses emphasize the distance between things, long lenses compress distances, in effect flattening the image. The result can be one of otherworldly elegance, as in the case of 1:42.08 and Lucas’s subsequent re-use of the technique in both his student and documentary work. It’s most notably perhaps in THX 1138, where it almost removes the sense of ferocious speed from the climactic tunnel chase. Despite barreling down the track towards the camera, like the cars and bicycles in the opening shot of 60 Cycles, the racing car and motorcycles are reduced to a slow swerve back and forth. The subjects of a an extreme long lens shot, be they cars, bicycles, horses or camels are nearly reduced from three-dimensional objects to shapes; a ballet of shapes in unnatural movement.

In 1:42.08 it mostly has a rhythmic effect, acting as a counterpoint to the frantic intercutting of gear shifting, instrumentations and closeups of the driver (all shots reused verbatim in THX 1138 and transposed into the X-Wings of Star Wars). In THX 1138 the same long shots manage to both make THX’s escape attempt feel almost impotent, as his supercar at first seems caught, unable to move; as well as imbue the pursuing robot police with a relentless sense of purpose, as their motorcycles glide inhumanely across the screen.

And just to hammer the point home, both sequences make use of the low POV shot of the road roaring underneath the car. And both THX and the driver of the yellow Lotus spin out at a critical moment, only to reengage in the race/chase.

But the final lesson, one that ended up defining much of the New Hollywood approach to filmmaking, was one of efficiency. Even though the crew of fourteen on 1:42.08 was large by USC standards, Lucas had the chance to see the production of Grand Prix, a big-scale Hollywood production fielding a 120-man crew, where as Dale Pollock notes in Skywalking, “The studio cast and crew retired to portable dressing trailers at the end of a day’s shooting, while Lucas and company headed for their portable sleeping bags.”[kl892, 3]skywalkingkindle. Lucas would run into a similar thing on the set of McKenna’s Gold soon after when he was filming another tone poem, 6–18–67, cementing his belief in old Hollywood as an irreparable engine of waste.

Ultimately 1:42.08 didn’t have the impact of some of Lucas’s earlier films, although it did reinforce the young director’s belief in the power of cinéma pur and in working outside of the system, not to mention being a dry-run for the climactic third act of THX 1138.