Look at Life (1965)

George Lucas's very first student film, an animated one-minute short which won numerous festival prices.

One of Lucas's earliest influences, Arthur Lipsett was an avant-garde Canadian at the National Film Board. His style had a tremendous impact on Lucas's early films, and The Force was rooted in his films.

From Lucas’ first film, the black and white motion-collage, A Look At LIFE, one of his largest influences was the Canadian filmmaker Arthur Lipsett, whose work would influence not only his path towards becoming an editor, but the very aesthetics of his student films and inform ‘The Force’.

Employed for a period of about ten years by the National Film Board in Canada, and nominated in 1961 at the age of 25 for an oscar in the short film category for his first film, Very Nice, Very Nice—which so impressed Stanley Kubrick that he wrote the young filmmaker, asking him to edit the trailer for Dr. Strangelove, an offer he declined—Arthur Lipsett was a force in his own right.

Lipsett was working at a time when independent avant-garde filmmaking did not exist in Canada, with a few isolated exceptions […]. In the absence of independent distribution and funding mechanisms before the late ’60s, many innovative young cineastes ended up at the NFB where salaries, equipment, budgets and some degree of creative freedom could be quickly obtained.[1]

The NFB, whose mission it was to ‘interpret Canada for Canadians’, was at the time one of the few places where young filmmakers could find not only a modicum of creative freedom, but also the necessary equipment and money to make their films. It did a pretty impressive job of bringing in young talent and putting their work in front of eyeballs throughout Canada as well as the US (at least in the film schools at the time).

Lipsett quickly gained a cult following for his collage-like short films, which often broke every rule in the book. Aside from the technical prowess they exude, they manage to also be deeply personal, pessimistic yet playful, freely criticizing society, politics and religion. Lipsett was a natural at his craft, unfortunately, he was as troubled as he was talented.

“He insisted that everything had a sound or a force field. He had that kind of intensified perception of things. I didn’t know anyone who paid that much attention to the world. It was this intense capacity for observation that later became unbearable for Arthur. He bought industrial ear-protectors because he couldn’t bear hearing things. He was just too sensitive. At first he got them because of noisy neighbors, then he began to wear them all the time. Inanimate objects had symbolic importance for him. His films made you see things you didn’t see otherwise.”[2]

The young Lucas was introduced to Lipsett’s probably most well known film, 21–87 during his first year at USC, where the film was part of the curriculum:

When Derek Lamb was director of animation at the NFB, he once presented a series of NFB films in California. George Lucas (“Star Wars”) later came up and inquired. “How’s Arthur Lipsett? He’s a very important guy.” Apparently 21–87 was a big influence on Lucas’ class at U.S.C.[2]

Walter Murch, Lucas’s classmate, longtime collaborator on both THX 1138 and American Graffiti (and widely held as one of the most influential editors in film history) describes Lucas’s reaction to Lipsett’s work:

“When George saw 21–87, a lightbulb went off. One of the things we clearly wanted to do in THX was to make a film where the sound and the pictures were free-floating. Occasionally, they would link up in a literal way, but there would also be long sections where the two of them would wander off, and it would stretch the audience’s mind to try to figure out the connection.”

Lucas threaded the film through the projector over and over, watching it more than two dozen times.[3]

“I said, ‘That’s the kind of movie I want to make —- a very off-the-wall, abstract kind of film.’ It was really where I was at, and I think that’s one reason I started calling most [college] movies by numbers. I saw that film twenty or thirty times.”[Chapter 2, 4]

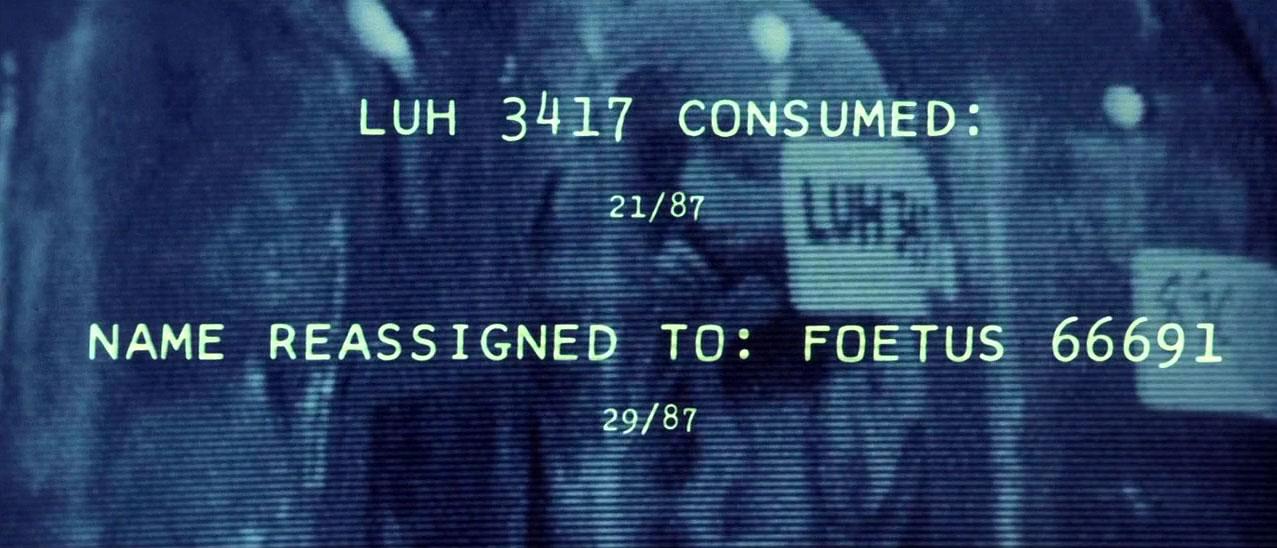

The title itself, 21–87 found its way into Electronic Labyrinth, as the year in which the film is set. In THX 1138 the title of Lipsett’s movie became the date on which THX’s mate, LUH–3417, was consumed. And finally in Star Wars, by way of Han: “We gotta find out which cell this Princess of yours is in. Here it is – 21–87”.

The chanting “Ooooom” preceding the eponymous soundbite “Bravo! Very Nice, Very Nice” from Lipsett’s film of the same name, might very well have become the Jesus-like icon OMM in THX 1138, religious imagery, mechanical arms handling fragile objects made their way into it as well, and of course the fragmentary nature and style of Lipsett’s soundscapes, which had originated from Lipsett’s fascination with sound tape (a fascination which later in his life turned into an overwhelming phobia), were the cornerstone in Murch’s work on THX 1138’s amazing soundtrack, including the choral music of 21–87 and the rapid drumming of Very Nice, Very Nice. Lipsett’s influence was enormous on the burgeoning filmmakers, and the off-the-wall, personal and almost spiteful attitude of his films was carried with them when they crossed over from film school, into the film industry.

The parallels between Lipsett and Lucas’s respective approaches to filmmaking go beyond mere style. Both make widespread use of adapting and reusing existing material; where Lipsett combined unrelated images and fragments of sound, Lucas instead recreated and mixed scenes, characters and genres. Both drew on the juxtaposition between, and the complementation of these elements to create something new. Though no one would guess it simply by looking at them side by side, the distance between 21–87 and Star Wars is infinitesimal.

Lipsett would use sound clips of politicians and other famous people, juxtaposed with his own images, or unused images from other people’s films as commentary. In a sense, Lucas and Lipsett used the same essential technique, drawing on something vaguely recognizable to create a similar sense of the retooled past. But where Lipsett’s films create commentary on its component elements, Lucas’s create something new. The same technique, but with contrasting purposes.

[Dennis Mohr, producer of Arthur Lipsett: Poet of Film] says he has no reason to believe that Lipsett was aware 21–87 had been referenced in Star Wars. Lipsett liked the movie, but Mohr’s research hasn’t turned up any evidence to suggest that Lipsett knew Lucas had symbolically tipped his hat in the Canadian’s direction. “It’s so small,“ Mohr says of the homage. ”It probably just went over most people’s heads until the ’80s."[5]

It’s an off-hand reference which in itself is irrelevant to the franchise as a whole, but 21–87’s contribution to The Force, was not. Lipsett’s movies struck a chord with Lucas’s search for a spiritual angle for his movies, ostensibly providing much of the religious atmosphere for THX 1138, and the generalized spiritual concept, as well as the name for, The Force. According to Wired sampled from “a conversation between artificial intelligence pioneer Warren S. McCulloch and Roman Kroitor, a cinematographer who went on to develop IMAX. In the face of McCulloch’s arguments that living beings are nothing but highly complex machines, Kroitor insists that there is something more.”[3] (emphasis mine):

“Many people feel that in sort of the contemplation of nature and in communication with other living things, they become aware of some kind of force, or something, behind this apparent mask, which we see in front of us. And they call it God, or they, or depending on their particular disposition. To the question…”

An interviewer interrupts, “Do you mean feelings or thoughts? Of some aspect of it?”

“Of some aspect of it… to me is not the same thing as a world full of human beings. There’s something gone. There’s something missing."

Another man, a seemingly unrelated sound clip, chimes in, “And then the people say, well this is God, let’s have more of it. And someone walks up and says, ‘your name is 21–87 isn’t it?’ and boy, does that person really smile.” [6]

Lipsett’s work didn’t so much influence Lucas’s early style, as it was his style. Lucas took it and ran with it wholesale, and then later built upon and to the side of it. Anything after that was Lucas slowly finding his own legs to stand on, as Look at Life, and arguably even the two versions of THX clearly show. Lucas and Lipsett shared more than their love of creating socio-political collages, as Lucas too was interested in anthropology and spirituality, much like Lipsett:

“[Arthur’s] range was vast. Everything interested him: Chinese dictionaries, Buddhist chants. He was trying to find universals in human culture, like an anthropologist. It was as if he, himself, were from another planet, looking at us all – as he did in his films. He was very smart and knew how society worked.”[2]

But, despite his love of Lipsett’s work, and a passing interest in the man behind them, ‘at no time did Lucas make a serious attempt to recruit Lipsett. “He didn’t really care about Lipsett the man so much as his films,” says Mohr. “He never did try to hire him or find out more about Lipsett personally.” In addition, Mohr says the rumour that Lucas considered coming to Canada to work for the NFB is unfounded, although it’s true he had a great deal of respect for the agency.’[5]

Noteably, Lipsett was but one of the artists making collage-like films at the time, including Saul Bass, whose Bell System Logo Redesign film probably owed a bit to Lipsett as well; or maybe just to the zeitgeist.

Lipsett himself may very well have been inspired in large part by Chris Marker’s defining 1961 time travel, photo essay movie La Jetée, which opens with choral music quite similar to that of Very Nice, Very Nice and Lucas’s student short Electronic Labyrinth. Told by a narrator and a series of changing photos (and a single snippet of film), it features a society living in a network of galleries underground. Here they carry out time travel experiments on their prisoners in an attempt to find relief outside of their own doomed time. Like Godard’s Alphaville and both of Lucas’s THXs, it made use of actual places and cheap props in creating a dystopian future world.

Unfortunately, over the years Arthur Lipsett’s output waned in quality and quantity as he fought mental illness and fell into depression.

He committed suicide in 1986, two weeks before his 50th birthday.

The National Film Board of Canada’s excellent website has all of Lipsett’s movies available for watching and purchase.

Arthur Lipsett, by Brett Kashmere. Sense of Cinema, issue 23. 2004. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

Lois Siegel. A Clown Outside the Circus. Cinema Canada, 1986.

Steve Silberman. Life After Darth. Wired.com. May, 2005.

Dale Pollock. Skywalking: The Life And Films Of George Lucas. Harmony Books, 1983.

Dan Brown. Star Wars: The Canadian Angle. CBC News Online, September 8, 2004.

Arthur Lipsett. 21–87. National Film Board of Canada, 1963.